“Homely Phrases”: Revisiting the Simplicity Paradox in George Herbert’s Poetry

If we hear the same old dove

Singing in the same old tree,

Might this bring us back to love

And beautiful simplicity?[1]

God only is, writes Thomas Browne, all others…are something but by a distinction. (Religio Medici, I, 35) To read Herbert’s poems is to experience the dissolution of the distinctions by which all other things are.[2]

When, in the closing pages of his Life of Abraham Cowley, Samuel Johnson berated the “ingenious absurdity” and “enormous and disgusting hyperboles” that he found in “a race of writers that may be termed the metaphysical poets”[3] he made claims that later commentators have been keen to refute. Johnson’s revulsion stemmed from his conviction that the human art of poetry was unworthy of taking God as its subject. Poetry was no substitute for prayer:

Contemplative piety, or the intercourse between God and the human soul, cannot be poetical. Man admitted to implore the mercy of his Creator and plead the merits of his Redeemer is already in a higher state than poetry can confer. […]

Omnipotence cannot be exalted; Infinity cannot be amplified; Perfection cannot be improved.[4]

The Lives do not mention George Herbert, but more than a hundred quotes from The Temple in the Dictionary suggest that Johnson did not judge Herbert solely as a repository of “metaphysical” poets’ faults. Moreover Herbert, who considered poetry to be, if not communion with God, at least a reflection, striving or foundation, enabled by grace, for intimate connection, was aware of its limitations: “Thou art still my God is all that ye / Perhaps with more embellishment can say.”[5] Johnson’s aversion captured the tenor of his times, which privileged an awareness, prefigured in Paradise Lost, of God’s distance and grandeur. Accordingly, no new Herbert edition appeared between 1709 and 1799.[6] The hiatus was filled by hymns, including “fifty-two Wesley adulterations” of The Temple’s poems.[7]

Since its first printed edition in 1633 many responses to The Temple’s literary, religious and political contents have been published. Coleridge, who found “substantial comfort” in Herbert’s “homely phrases,”[8] sparked a Romantic revival which developed in the twentieth century into the scholarly industry that still continues. Throughout this long engagement, simplicity is the single quality of Herbert’s poetry that commentators have praised, expounded, questioned, debated or denied. The first printer’s address to the reader set the trend, when the author, probably Herbert’s friend Nicholas Ferrar, noted his renunciation of classical allusions in favour of the Bible:

The world shall therefore receive it in that naked simplicitie with which he left it, without any addition of support or ornament, more then is included in itself.[9]

In 1997 Elizabeth Clark published a precise delineation of Herbert’s theology that superseded other attempts, partly by focusing on simplicity as an ideal that Herbert embraced, adapted from Savonarola’s De Simplicitate Christianae Vitae (1496).[10]

This essay delineates a way of reading Herbert by tracing in The Temple a simplicity which, while undeniably real, and sourced as Clark and others have proven, derives its power from a spirituality that in its essence is unlimited by dogma. Through this approach I hope to commend Herbert’s poetry to present-day readers, unschooled as we mostly are in theological niceties and burdened as our lives seem to be by multiplying complications.

Of all the commentaries, I regard T. S. Eliot’s poetic rendering to be the truest reflection of Herbert’s intentions when, close to death, he submitted The Temple to Ferrar’s judgment. In 1942 Eliot published the last of Four Quartets as a memorial to the Anglican community in Huntingdonshire that Ferrar had founded. Accordingly, when in “Little Gidding” Eliot famously redefined simplicity as a spiritual goal, he probably had The Temple in mind. “[T]he end of all our exploring,” he writes, will be “A condition of complete simplicity / (Costing not less than everything).” These lines occur in the closing sequence of allusions, symbols, metaphors and paradoxes through which Eliot, like Herbert, strives to ground the sacred in poetic language. The free modernist form of Four Quartets differs markedly from the rhymed and shaped verses of The Temple, but Eliot’s objective is the same as Herbert’s. “A condition of complete simplicity” evokes a perfected state of being equivalent to the union of suffering and love, and of spirit and flesh. Affirmed by a quote from Julian of Norwich’s Revelations, and imaged in the entwining of fire and rose, the last word of Four Quartets reaches beyond simplicity to oneness as the ultimate goal:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.[11]

I contend that when Eliot identified “complete simplicity” with the oneness of the sacred and “the end of all our exploring,” he paid tribute to Herbert by remodelling for modern readers a progression that pervades The Temple.[12] In both collections poetic beauty summons readers on a pilgrimage to the divine oneness. Oneness attained, there is no more to say: all that is not music is silence.[13]

Critics and poets have praised the simplicity of Herbert’s art while insisting on its complexity, often without acknowledging a contradiction. In attempting another approach,[14] my purpose is to trace the multiple processes of Herbert’s renunciation, by which poems in The Temple generate insights into divine reality as simple but all-encompassing. In envisaging creation as united in a single, unceasing act of praise “Providence” expresses what was probably Herbert’s deepest conviction:

Thou art in small things great, not small in any:

Thy even praise can neither rise nor fall.

Thou art in all things one, in each thing many:

For thou art infinite in one and all. (lines 41-44).

This is a version of monism, central to Hinduism, Sufism and Yoga, but also compatible with the one God proclaimed in Old and New Testament texts.[15]

In accordance with their importance to Herbert’s theology, many kinds of simplicity nevertheless pervade The Temple, and oneness also yields a range of definitions. Much of Herbert’s verse is “homely,” reflecting a life that, unlike those of most of his relatives and peers, was passed wholly in England.[16] Readers of the eleven editions of The Temple printed before 1700[17] were often middle class, and the book is dedicated not to a noble patron but to God. “New Year Sonnets” (I) and (II), which predate The Temple, and “Love” (I) divert the art of the love lyrist to God’s praise, while poems such as “Jordan” (I) renounce and critique the sophisticated traditions of fin amour. Ubiquitous Bible allusions are another feature of The Temple’s simplicity, to be welcomed by readers for whom access to the Bible in English was a new and still contested freedom.[18] Herbert encourages readers to explore his ideas independently, while assuring them of Anglican orthodoxy by constant recourse to Biblical texts and forms, including parables, stories, praises, proverbs, poems and songs.[19] Chana Bloch and Helen Wilcox confirm that the Book of Psalms, which Herbert read through each month at evening and morning prayer, was his main Biblical source. Conversely, classical allusions are, as Ferrar forewarned readers in his Proem, rare or occluded in The Temple.[20] Further restraints that Herbert adheres to include simplicity of syntax and vocabulary, the latter perhaps most striking in repetitions of common monosyllabic words: “sweet,” “box,” “dust,” “rest,” “mirth,” etc.[21] Some poems, such as “Praise” (II), which was quickly adapted for congregational singing, are simple at all levels.[22] The lengths to which Herbert was prepared to go in the cause of simplicity, which he saw as redemptive for both himself and his readers, is evident in “Discipline,” where a monosyllabic vocabulary, uncomplicated sentence structures, repetitions with variation, and strictly placed two- and three-syllable lines epitomize the quality valued in the title.

Meanwhile an overarching tripartite structure gives fluid shape to a collection that encourages deep contemplation of individual poems—an intention that the reading history of The Temple supports: “[t]he simplicity of their appearance does not accompany simplification of idea.”[23] Despite this, the simple internal logic and meticulous development of every poem in the long middle section “The Church” are acts of humility that support the genuineness of Herbert’s wish to benefit every reader irrespective of status, wealth or education. As he writes when revisiting in “Faith” the yearning for oneness that pervades his work: “One size doth all conditions fit. / A peasant may believe as much / As a great Clerk, and reach the highest stature.”

A Quest in Poetry

“The Church-Porch,” the long introductory section which Herbert composed twenty years before Ferrar named[24] The Temple, decorates its Polonius-like messages on morals and manners with alliteration, antitheses, personifications, similes, puns, and metaphors. “The Church Porch” also reveals however, that even by his early twenties Herbert aspired to poetic virtuosity for the sake of insight and instruction, and that he intuited the potential for luminous art that lies in simplicity. He likens the latter to the joy underlying creation itself:

All things are bigge with jest: nothing that’s plain,

But may be wittie, if thou hast the vein.

Accordingly, in most of his poems written later, Herbert’s masterly combining of verbal simplicity with witty poetic forms that invite descents to ever deepening layers of meaning explain The Temple’s appeal over centuries to readers of varying beliefs, and with differing opportunities for reading and education. “Lent” typifies poems in “The Church” that revert to the simple preaching style of “The Church Porch”: they are homilies to ordinary, possibly new or newly converted, Christian readers. For Herbert, wit, like poetic quality, depends ultimately on God’s approval, as in “The Forerunners”: “if I please him, I write fine and wittie.”

While not referring directly to either simplicity or sacred poetry, “Prayer” (I) deploys mimesis brilliantly in an argument for combining the two. Abstractions like “soul,” “softnesse,” “love,” “bliss,” and “gladnesse,” and the martial, cosmic, and heavenly metaphors and paradoxes of this sonnet’s twenty-six epithets for prayer, many of which refract grand utterances in the Bible, descend suddenly to earth in the twenty-seventh, which consists of two words: “something understood.” This first grammatical passive reverses the energetic aspiration implied by an epic phrase like “[e]xalted manna” and embodies the ending’s sudden switch from a human struggle towards a being of infinite greatness to a restful acceptance of grace. At the same time, the modesty of this final hope for a single God-given insight exemplifies the drive of many of Herbert’s poems towards oneness. Here it opens prayer as a practice for every reader, however humble. It deflates any overweening expectations raised by the majestic epithets that precede it. This grounding of the sacred in what is simple, human, real, and recognisable is fundamental to the poetic accomplishment of Herbert’s most moving poems.

Seven lyrics in “The Church” address simplicity directly as a poetic goal, and most of them seek oneness with God as a longed-for consummation. In the order of the 1633 edition, they are “Jordan” (I), “The Quidditie,” “Jordan” (II), “A True Hymne,” “The Forerunners,” “The Posie,” and “A Wreath.” These form a component subordinate to the central drama of The Temple, which is the poet-speaker’s struggle to accept grace and come to Christ, the one embodiment of all perfections, as stated in “Dulnesse”: “Thou art my loveliness, my life, my light, | Beautie alone to me.”

“Jordan” (I) simultaneously describes and mimes, both the elaborate romantic and pastoral styles that the speaker rejects:

Is it no verse, except enchanted groves

And sudden arbours shadow course-spunne lines?

Must purling streams refresh a lover’s love?;

and the simple verse that he practices: “Who plainly say, My God, My King.” The speaker adopts a challenging, confident tone, as if Herbert’s commitment to plain speaking, the baptizing of his muse, and devotion to “truth,” the Platonic inner essence of things, caused no difficulty and came at no cost.

“A True Hymne” refutes this by revisiting the frustrations of a day in which the automatically repeating phrase, “My joy, my life, my crowne,” has blocked invention. Yet stanza 2 affirms that “these few words,” “when the soul unto the lines accords,” are “[a]mong the best in art” and that this oneness of the creating self with what is created is the “finenesse which a hymne or psalm affords.” The implication, reaffirming the title, is that truth simply expressed is better than invention, and that a hymn, which the title shows this poem has become, is a worthier work of art than a poem. The two remaining stanzas adopt God’s perspective, further adjusting the argument of “Jordan” (I) by asserting that God, who craves the heart’s, soul’s and mind’s devotion (Luke 10. 27), will reject “verse” that succeeds merely as words,

Whereas if th’ heart be moved,

Although the verse be somewhat scant,

God doth supplie the want.

Rather than flaunting his “plain” style as in “Jordan” (I), Herbert here declares that God endows a heart-felt poem with beauty and wholeness. The argument is dramatized in the closing dialogue, in which the heart sighs to love God, who, participating at last as a fellow poet, reduces simplicity to oneness with the single word, “Loved.” Despite their differences, both poems testify that Herbert esteemed simplicity as sufficiency.

Yet Eliot affirms that simplicity costs “not less than everything.” Accordingly, in both “Jordan” (II) and “The Forerunners” the speaker finds it painful, first to allow the whisper of a “friend” (Christ) to direct, and secondly to persuade himself, to pay the price. “Jordan” (II) narrates and embodies in words the beginning and early stages of the poet’s struggle between the egotistical invention of “quaint words,” the “thousands of notions” with which he sought “to clothe the sunne,” and the simple receptivity of “copying out” the “sweetnesse” in love. In “The Forerunners” by contrast, the struggle for simplicity in composition, sparked by the onset of old age (as Herbert, not yet forty, sees it), is conducted passionately in the present tense:

Louely enchanting language, sugar-cane,

Hony of roses, whither wilt thou flie?

The conflict is resolved by again resorting to Plato with the argument that since God is beauty, beauty in verse is worth striving for, provided that God is the subject:

True Beautie dwells on high: ours is a flame

But borrow’d thence to light us thither.

Beautie and beauteous words should go together.

Alone in The Temple, “The Quidditie” upholds the making of sacred poetry as a redemptive act in itself. It thereby disputes the doubt entertained in “The Forerunners.” Originally titled “Poetry,” Herbert’s amendment clarifies his poem’s subject as being the singular essence, not the diversified all, of poetry: “quiddity” (Latin quidditas) means “the essence of things.” Negatives in lines 1 to 10 contrast this singular creative purity with the scattering and busy-ness of kingly, courtly, sporting, and money-making pursuits. Like “A True Hymne” they deny that sacred verse is merely an art. Instead “The Quidditie” concludes that the writing of such verse is a total surrender— Most take all — that unites the speaker with God — “I am with thee” — thereby once again reducing multiplicity to oneness.

In “The Posie,” sequenced near the end of “The Church” and punning on “poesie,” Herbert’s dismissal of poetic virtuosity in favor of the single scriptural motto which, according to Walton, he used to describe The Temple, is just as definite:

Invention rest,

Comparisons go play, wit use thy will:

Lesse then the least

Of all Gods mercies, is my posie still.

Simplicity as a poetic goal could hardly be more clearly affirmed.

My seventh example, “A Wreath,” forms a hinge between the five eschatological poems that conclude “The Church” — “Death,” “Dooms-day,” “Judgement,” “Heaven,” and “Love” (III) — and the 156 poems that precede it. “A Wreath” moves on from Herbert’s verse “Dedication” of the whole of The Temple to God by contrasting the convolutions of sin and deceit which lead to death with simplicity, cognate with straightness and life. Both the form and the content of his urgent plea — “Give me simplicitie, that I may live” — testify to the genuineness of his longing, and “A Wreath” is expressed in simple words and syntax. Paradoxically however, like many Temple poems its form is complex — an adroit imitation with reversed repetitions of the interwoven strands of a wreath, achieved through the device of reduplicatio. Wilcox’s commentary uncovers more devices and lists classical and Renaissance precedents, as well as Herbert’s usual contingent of semi-submerged Biblical allusions.[25] Yet this artistic depth and richness, bringing delight to readers and surely to Herbert himself, “A Wreath” lumps together with the first-person speaker’s “crooked winding ways” under the heading of “deceit,” which falsely “seems above simplicitie.” Herbert’s fascination with one-pointedness — i.e. a singular focus — as a moral, as well as a spiritual, practice and goal is here apparent, as it is also in “Constancie,” which praises the “honest man” as one whose “words and works and fashion too” are “[a]ll of a piece, are all clear and straight,” and who “above all things…abhorres deceit.” “A Wreath” finally critiques its own artistry, and, by extrapolation, questions the integrity of the whole of The Temple as a poetic endeavour. A similar humility is evident elsewhere, for example in “Employment”:

All things are busie; onely I

Neither bring hony with the bees,

Nor flowres to make that, nor […].

The interruption that ends “Dialogue” – “Ah! No more: Thou breakst my heart!” once again sacrifices the pattern of argument in order to subordinate art to spiritual quest. As in “A Wreath,” fears of fruitlessness and bad faith explain why Herbert in extremis committed The Temple to Ferrar’s judgement.

The struggle for simplicity in verse-making is therefore an area in “The Church” where the drive for oneness flourishes, and Herbert is endlessly resourceful in finding analogies.

A Congregational and Priestly Quest

The fascination with oneness in diversity in The Temple may stem from Herbert’s Trinitarian theology, a belief that persists as a mystery — a kind of koan — to Christian believers. In a reversal that testifies yet again to the intensity of his struggle to sanctify his creative gifts, “Easter” transforms the interwoven strands seen as “deceit” in “A Wreath” into polyphonic praise with a Trinitarian significance:

Consort both heart and lute, and twist a song

Pleasant and long:

Or since all musick is but three parts vied

And multiplied;

O let thy blessed Spirit bear a part,

And make up our defects with his sweet art.

“Easter” typifies poems directed to Herbert’s Bemerton congregation, sequentially failing in praise through music, nature, and rhetoric, but progressing in the last stanza from segregated time to the seamlessness of eternity, and from the many to the one:

Can there be any day but this,

Though many sunnes to shine endeavour?

We count three hundred but we misse:

There is but one, and that one ever.

Here as often, superficial wit—the pun, Sun/Son and the contrast between numbered earthly days and heaven’s infinite but single day—serves profoundest spirituality. Elsewhere musical harmony is as significant as verse simplicity in the drive towards oneness, for example in “The Thanksgiving”:

My musick shall find thee, and ev’ry string

Shall have his attribute to sing;

That all together may accord in thee,

And prove one God, one harmonie.

“Trinitie Sunday” is a prayer in poetry which once again mimes the speaker’s desire for oneness with God. A virtuoso play in tercets and triplets on the numbers one and three, the opening and closing words: “Lord, […] That I may runne, rise, rest with thee” [italics added] embody in words the unity attributed to the triune God and the speaker’s wish to share in it. This poem’s simple words make the mystery of divine being accessible to a congregation at different levels of poetic engagement. By contrast “The Call,” a three-stanza monosyllabic poem likewise arranged ingeniously in threes, concretizes its plea to the Trinity through repetitive simple prayers: “Come, my Way my Truth, my Life […].” For Helen Vendler, “The Call” is “a touchstone for one’s attachment to Herbert” and one’s reactions to his wish for “simplicity-in-complication.”[26] Yet although here as elsewhere Herbert does indeed practise “simplicity-in-complication,” a reader can see this as a response to the exigencies of his art, and can choose, as with “Trinitie Sunday,” to engage rather than to analyse. Finally, the Trinitarian theology of “Affliction” (III) is denser than commentary so far reveals. Stanza 1 affirms God the Father’s indwelling in the speaker’s grief; stanza 2 identifies his breath with the creative power of the Holy Spirit; and stanza 3 speaks of the infinite indwelling of the crucifixion in each believer — “thy members,” of whom the speaker is one. “Affliction” (III) thus expresses humans’ oneness with God as an ongoing truth.

As they proceed in concept and words through complexity to simplicity and from simplicity to oneness, some Temple poems overcome divisions in social and intellectual life. They even challenge, if fleetingly, the preordained positioning of beings in the hierarchy of creation. Befitting Herbert’s pastoral mission, the quest for unity in the mostly monosyllabic “Antiphon” (I), based on Psalm 95.1-6, and intended for responsive choral singing, is alternately priestly and congregational. The first stanza particularizes heaven and earth, the second the Church and the individual Christian, but the chorus, sung three times, draws creation into a unified act of worship: “Let all the world in ev’ry corner sing, / My God and King.” The similar movement of “Antiphon” (II) again unites the earthly and heavenly choirs: “Praised be the God alone, / Who hath made of two folds one.”

Equally true to Herbert’s pastoral mission but unusually acerbic, “Divinitie” mandates a simple faith that obeys New Testament commandments rather than the convolutions of reason. Despite his intellectual attainments, in religion Herbert looked first to revelation: “Faith needs no staffe of flesh, but stoutly can / To heav’n alone both go, and lead,” a priority that resurfaces in “Faith.” “Divinitie” likewise “reduces Christianity to its first elements — “love, watch, pray, do”:[27]

Love God, and love your neighbour. Watch and pray.

Do as ye would be done unto.

O dark instructions; ev’n as dark as day!

Who can these Gordian knots undo?

Also addressed to parishioners, “An Offering” suggests that oneness may be pleasing to Christ. Oneness features in this poem in various forms: the singleness of a pure heart; the union of the divine and human in Christ; the healing of divisions created by desire; the Passion as the healer of “[a]ll sorts of wounds”; and finally the holistic offering of the speaker’s heart to God alone. The pattern is repeated in “Vanitie,” where earthly knowledge, outward multiplicity, and physical immensity, searched through by the Astronomer (stanza 1), the Diver (stanza 2), and the Chemist (stanza 3), are countered by inward simplicity and oneness — their “deare God” whose law is nurtured in each person’s heart.

Many Temple poems have been adapted as hymns, others are a bridge to meditation, and some are both. The simple Bible-based prayers and ejaculations — “Thou art still my God” in “Antiphon” (I), “My God, My King” in “Jordan” (I), “My joy, my life, my crown” in “A True Hymne,” and Herbert’s motto discussed above — are the obverse of the “sublime” as exemplified in the orotund quote from Johnson that begins this essay. For readers like Eliot, learned in European and Eastern spiritual traditions, Herbert’s mottos invite understanding as mantras—phrases chanted or silently repeated to focus and still the mind, in everyday life as in meditation. In this respect Herbert, the archetypal C of E poet, oversteps his sectarian bias and moves towards ecumenism. Indeed, at the level of sacred experience to which Herbert’s poetry repeatedly calls his readers, divisions of any kind, whether religious or secular, would seem to be meaningless.

Spoken by either or both priest and communicant, “The Agonie” exemplifies the contracting and expanding progression of many poems in The Temple.[28] Stanza 1 reduces the vastness of the universe, both perceived and transcendent, to “two, vast spacious things”— Sin and Love. The contraction, agonising in stanza 2: “Sinne is that presse and vice, which forceth pain / To hunt his cruell food through ev’ry vein,” is released in the last stanza, which is full of flowing liquids: “juice,” “liquour,” and finally the “bloud” of the crucified Christ. All are metonyms, the reader at last discovers, for “Love,” the single word that unifies the sequence and pervades The Temple as the most ubiquitous of Herbert’s repetitions.[29]

In respect of the priestly office, “The Windows” looks for a oneness in the preacher that transmits to the congregation without a need for words: “Doctrine and life, colours and light, in one / When they combine and mingle, bring / A strong regard and awe” [italics added]. Similarly, “Aaron” traces Herbert’s re-formation as a priest through his sequential putting on of and union with St Paul’s “new man,” culminating in a celebration of his oneness with Christ himself:

Christ is my onely head,

My alone onely heart and breast,

My onely musick, striking me ev’n dead;

That to the old man I may rest,

And be in him new drest. [italics added]

Existing beyond but also encompassing the priesthood, Herbert saw each person’s life as a unity. The ending of “Mortification” makes one “life in death” of the many dyings that comprise experience. In “Coloss. 3. 3,” the simplicity of the Biblical text, “Our life is hid with Christ in God,” encapsulates the oneness with Christ that underlies the “double motion” that human lives share with the sun, here conveyed by play with rhymes, alliteration, metaphors and antitheses.

Analyses in this section support the contention that themes of simplicity and oneness in The Temple, expressed through Trinitarian theology, rejections of multiplicity in created being, convergences on a single goal alike for the priest and his congregation, and a longing for union with Christ, are central to Herbert’s vision.

A Personal Quest

As well as a way of fulfilling pastoral obligations — and the continuing appeal of The Temple shows that for centuries readers have readily identified with Herbert’s quest — creating poetry was for him spiritual training, undertaken in the hope of receiving insight and ultimately salvation. In accordance with his Calvinist theology, he regarded the latter as divinely predestined, and his writings suggest that Herbert came to trust in his own election only shortly before his death. Accordingly, many of the meanings conferred on “one” as both pronoun and number in The Temple indicate or replicate the divine singleness as the healing sought by a scattered self.

Another example of mimesis, the consummation of “JESU” uncovers a oneness shared by the sacred name, the speaker’s restored wholeness, and Jesus himself: “and perceived / That to my broken heart he was I ease you, / And to my whole is JESU.” Simple colloquial language delivers this poem’s conceptual ingenuity. Similarly, “The Sonne” puns on the “one onely” name that we give to the sun—“parents issue” and “The Sonne of Man.” In Herbert’s best-known poem, “The Collar,” an increasingly chaotic dialogue consisting of exclamations and rhetorical questions, between the rebel heart and the strategizing will, is resolved by a single-word intervention that restores unity, both between Christ and the speaker, and within the speaker: “Me thoughts I heard one calling, Childe: / And I reply’d, My Lord.” The reader can choose to interpret the Biblical metaphors and the allusions to the instruments of redemption – communion table, thorn, blood, wine, corn, fruit – that promise from the beginning to undermine the revolt, or to join in the powerful flow of anger that is cut short by this simple dialogue. By conjuring oneness from multiplicity and division, the ending to “The Collar” repudiates both the revolt and the metaphors in which it is expressed, as if Herbert were striving once again, as in “Trinitie Sunday,” to suppress or make secondary the complexity of allusion that marks much of his verse. His view in “The Collar” of childhood simplicity as redemptive (Matthew 18.3) resurfaces in “H. Baptisme” (II) which applies the proposition, “Childhood is health,” to the speaker’s early and present life. Simple words and syntax in the often-anthologized “Even-Song” likewise epitomize a child-like trust:

My God, thou art all love.

Not one poor minute scapes thy breast,

But brings a favour from above;

And in this love, more then in bed, I rest.

Another instance of Herbert’s monism, “Clasping of Hands” adroitly describes in simple words the dissolution of dualisms and distinctions into a oneness passionately prayed for as an attainable end. The vocabulary is repetitive, sequentially narrowing definitions of “mine” and “thine,” until the Christian and God do not merely “clasp hands” but merge. The ending prays for mutual possession— “O be mine still! Still make me thine!” and then for the extinction of boundaries, for identification between God’s and the speaker’s beings—“Or rather make no Thine and Mine!” The state so fervently desired transcends paradox.[30] In the two stanzas of “Easter Wings” the shortest centre lines praying for resurrection “[w]ith thee,” sequentially for humanity and the poet, restate the objective of oneness with Christ which is the goal of The Temple. “The Search” evokes the same goal even more clearly:

For as thy absence doth excell

All distance known:

So doth thy nearnesse bear the bell,

Making two one.

Adapted as a hymn by John Wesley, “The Elixer” by contrast is theologically conservative, since it assumes God’s universal indwelling but maintains separateness of being: “Teach me, my God and King, / In all things thee to see.”

Herbert’s poetic and actual struggle for simplicity and oneness also takes time into account. According to The Cloud of Unknowing (circa 1380), God’s felt presence is simple because it is fleeting — an atom of time in which heaven is won and lost. Therefore “nothing is more precious than time.”[31] The Temple bears similar witness to the brevity of God’s felt presence. For example “The Discharge” recommends a unified focus on the present moment, not on the past, nor the future, nor on the thought of death:

Man and the present fit: if he provide,

He breaks the square.

This houre is mine: if for the next I care,

I grow too wide,

And do encroach upon death’s side.

The advice, found in many spiritual traditions, is to simplify thinking by focusing on the here and now. The goal is mental stillness.

Yet Herbert often laments the transience of such states of simple awareness: “But one half houre of comfort for my heart?” (“The Glimpse”); “What doth this noise of thoughts within my heart […]?” (“The Familie”); ‘Killing and quickening, bringing down to hell / And up to heaven in an houre” (“The Flower”); “A mirth but open’d and seal’d up again” (“The Glance”). “The Glance” is in fact devoted to the theme of God’s momentary presence, when “one aspect of thine” [shall] “spend in delight / More then a thousand sunnes disburse in light.” Yet this illumination is preceded and followed by struggle and suffering—the unceasing changes that maintain the illusion of a time-bound separate being. In “The Flower,” written during one such “sweet return,” Herbert nevertheless asserts that the divine perspective, which is truth, rules and encompasses time and being itself: “We say amisse, / This or that is: / Thy word is all, if we could spell.”[32]

Indeed, self-correction is a frequent strategy in The Temple as Herbert brings his complex self into unity in an effort to restore Edenic obedience and love. “Affliction” (I) pivots on a contrast between the divine oneness manifested in Christ’s single act of redemption, and the all-ness, the multiple sins and griefs of humankind, experienced by the speaker—“Thy crosse took up in one, / By way of imprest, all my future mone.” Founded on the parable of the merchant who sells “all that he had” to buy “one pearl of great price” (Matthew 13.45-46), the unificatory drive of “The Pearl” sweeps up learning, honour, pleasure, Zeus’s golden rope for hauling earth up to heaven, Jacob’s ladder, Christ’s cross, and Ariadne’s cord into the oneness of “thy silk twist let down from heaven to me.” The last stanza reduces the labyrinthine analogies to the monosyllabic simplicity of “To climbe to thee.” The vehicle is grace, not striving, and the goal is again oneness with God. The ending moves without tension from this world to heaven, between the reality perceived by the senses and the inner kingdom of the heart.

The drive for unity is equally apparent in “Affliction” (IV), which begins with an agonized “scattering” that again recalls the Cloud-author’s language: [33]

My thoughts are a case of knives,

Wounding my heart

With scatter’d smart, […]

but ends by envisioning an integration of the self towards oneness with Christ, in a manner that presages “Love” (III):

Then shall those powers, which work for grief,

Enter thy pay,

And day by day

Labour thy praise, and my relief;

With care and courage building me,

Till I reach heav’n, and much more thee.

A similar sequence occurs in “The Temper” (I), where early stanzas evoke cosmic, ethical and emotional stretching and scattering, warfare and division: “Wilt thou meet arms with man, that thou dost stretch / A crumme of dust from heav’n to hell?” The turning point is the surrender in stanza 6, “Yet take thy way; for sure thy way is best.” A musical metaphor settles the disjunctions: “This is but tuning of my breast, / To make the music better,” until in the last stanza dualisms — geographical and inter-personal distance, heavenly angels and earthly humans — are subsumed in a vision of the oneness of all things, as the speaker finds rest in the care of a loving Creator:

Whether I flie with angels, fall with dust,

Thy hands made both, and I am there:

Thy power and love, my love and trust

Make one place ev’ry where.

The chiasma renders the oneness of God’s and the speaker’s love pictorially: “Thy power and love, my love and trust.”

Cosmic distances contract similarly in “Redemption,” as the speaker searches heaven and rifles earthly scenes of pomp and circumstance, but finds only one source of deliverance—the death of Christ. The critical consensus regarding another allegory, “The Quip,” is that the simplicity of the refrain, “But thou shalt answer, Lord, for me,” exposes the irrelevance of the worldly personas’ posturing. Yet the language is simple throughout, and Herbert’s early readers would have easily interpreted the emblems—Beautie /rose; Money /chinking [coins]; Glorie /expensive silks; Wit and Conversation /oration. The final exchange of mutual love, “say, I am thine,” is as simple as it is complete. Similarly, in “The Holdfast” a closing paradox draws the speaker’s complex strivings—his obedience, trust, and spiritual helplessness and poverty—into oneness and the keeping of Christ: “all things were more ours by being his.”

Sometimes, as suggested above, Herbert’s quest for simplicity and oneness in The Temple transforms into a longing for the wordlessness of meditation. “The Thanksgiving” grounds this sequence in experience, when music with its one-making power, Bible reading, and finally words fail the speaker as he searches for a way to respond to Christ’s sacrifice:

Then for thy passion—I will do for that—

Alas, my God, I know not what.

Similarly, the infrequently discussed poem “Frailtie,” rejoices in the transitory freedom from desire for “honours, riches, or fair eyes”— “[…] fair dust”—that the poet experiences “in my silence,” i.e. the wordless meditative space. “Grief” by contrast speaks his despair when tears, poetry, music, and lastly dialogue with each of these expressive media prove deficient. The “final cry” is, as Strier perceives, “a rejection of language itself”:[34]

Verses, ye are too fine a thing, too wise

For my rough sorrows: cease, be dumbe and mute,

Give up your feet and running to mine eyes,

And keep your measures for some lover’s lute,

Whose grief allows him musick and a ryme:

For mine excludes both measure, tune, and time.

Alas my God!

Art and its accoutrements lose their power in the dark night of the soul. After “Alas my God!” all that remains is silence: what the intellect fails in, that is God.[35] The eloquent Herbert here tends once again to the apophatic.

The monosyllabic close to “Love” (III), the last poem in The Temple’s middle section, perfects the sequence. Simone Weil testified to the power of “Love” (III) when she recalled:

I discovered the poem of which I read you what is unfortunately a very inadequate translation. It is called Love. I learned it by heart. Often, at the culminating point of a violent headache, I make myself say it over, concentrating all my attention upon it and clinging with all my soul to the tenderness it enshrines. I used to think I was merely reciting it as a beautiful poem, but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer. It was during one of these recitations that, as I told you, Christ himself came down and took possession of me.[36]

For most readers “Love” (III) enacts the poet-speaker’s final surrender to Christ’s service, now viewed as ultimate fulfilment:

Know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My deare, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

Apart from the endlessly resonant personification “Love,” the “complete simplicity” of these lines falters only over the verb “serve,” which here combines the sense of “obey, surrender” with that of “serve the purpose, be good enough.” “Serve” thereby embodies the reciprocity demanded by a whole-hearted acceptance of grace, a theme which, often exemplified above, pervades The Temple and is this poem’s controlling idea. The last line captures the moment when the sometimes-theatrical dualisms of dialogue and conflict frequent in “The Church” give way to oneness with Herbert’s Christ-God-Love. “Love” (III) thus crowns the many attempts made by The Temple’s poems to achieve formal and spiritual oneness. Where earlier poems succeed in this, the resolutions are temporary and later the struggle resumes. At the end of “Love” (III), however, dialogue and words themselves are subsumed into the simple homely actions of sitting and eating, and the resolution is infinitely ongoing.

Conclusion

Herbert’s masterly combining of verbal simplicity with witty rhetorical and poetic forms that induce descents to ever-deepening layers of meaning explain The Temple’s appeal over centuries to people of varying or no belief, and with differing opportunities for reading and education. Words like “grones” and “weed” in “The Crosse” and elsewhere, unpoetic to readers now and possibly to Herbert’s contemporaries, guarantee that The Temple is grounded in simple things and honest, unromantic feeling. Herbert is no more a romantic like his admirer Coleridge, than he is a classicist like his critic Johnson. “The Crosse” ends by claiming for the speaker the words of Christ: Thy will be done. No answer to the inner turmoil otherwise unrelieved in this poem could be simpler, more eloquent or, if practiced, more costly.

Analyses in this essay have shown that, like the ending of “Little Gidding,” many Temple poems reduce complexity to simplicity and simplicity to oneness. Because it entails a state that transcends language and therefore error, oneness is equivalent to silence. While simplicity in various forms and to varying degrees is a fluctuating presence in Herbert’s poetry, it is less often pursued as a theme. Oneness by contrast is pervasive, both as a concept and as the goal to which everything, including poetic virtuosity, tends. Oneness with God, for creation as for himself, is Herbert’s vision, just as centuries later it was Eliot’s. This essay has argued that it is precisely this quest, prominent in so many of Herbert’s poems, that Eliot flatters by sincerest imitation in Four Quartets. For both poets, a simple reidentification of the self with God—the making of two one—is the pearl beyond price for which more or less elaborate poetry is the setting. Like the ending to “Little Gidding,” the “Envoy” to The Temple prays for an ultimate redemption of creation through an embrace of the divine oneness: “Blessed be God alone, / Thrice blessed Three in One.” This prayed-for oneness, identified with the silence that ends the book, nourishes but finally incorporates distinctions, just as the simplicity dynamic, in Herbert as in Eliot, dedicates complex poetic art to the one source of all beauty.

NOTES

[1] Leunig, https://ko-kr.facebook.com/MichaelLeunigAppreciationPage/photos/a.17507561 .

[2] Fish, “Self-Consuming Artefacts,” 158.

[3] Johnson, Lives, “Abraham Cowley,” Vol. 1, 11, 13, 17.

[4] Ibid., “Edmund Waller,” Vol. 1, 173-74.

[5] “The Forerunners,” lines 32-33; Wilcox, English Poems, 612. Page and line references to Herbert’s writings in this essay are to Wilcox’s edition.

[6] Hutchinson, Works, xlvii.

[7] Rickey, Utmost Art, 149.

[8] Coleridge, Collected Letters, letters 1159 and 1524.

[9] Wilcox, English Poems, 41-42.

[10] Clarke, Theory and Theology, Chapter I.

[11] Eliot, Collected Poems, 222-23.

[12] Eliot’s criticism validates the debt to Herbert’s simplicity that is enshrined in his poetry:

It is to be observed that the language of these [Metaphysical] poets is as a rule simple and pure; in the verse of George Herbert this simplicity is carried as far as it can go—a simplicity emulated without success by numerous modern poets. (Times Literary Supplement 20 October 1921, 669–70)

Eliot included himself among these poets. In a booklet published in 1962 he characterized Herbert as ‘the master of the simple everyday word in the right place’ (George Herbert, 34).

[13] George MacDonald, Unspoken Sermons, ed. Sloane, 70.

[14] My argument is compatible with, but remakes and recontextualizes, Fish’s chapter cited in endnote 2 above. Fish’s work on Herbert, like that of many critics of the former and present century, repays revisiting.

[15] Deuteronomy 4.6: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord”; Mark 12.29: “And Jesus answered him, ‘The first of all the commandments is, Hear, O Israel; The Lord our God is one Lord’.”

[16] Herbert’s fourteen-line Latin poem “Ad Deum” compares the abundance of inspiration provided by the Holy Spirit to the seasonal over-flowing of the River Nile (McCloskey and Murphy, Latin Poetry, 60-61). Such exoticism is rare in The Temple, except in references to the Bible. Herbert envisaged readers who, like himself, had not traveled abroad.

[17] Wilcox, English Poems, xxxix.

[18] Wilcox’s “Index of Biblical References” (720-32) re-calibrates Chana Bloch’s already impressive lists and exposes yet more implicit and explicit allusions.

[19] Wilcox, English Poems, 726.

[20] Rickey, Utmost Art, devotes Chapter 1 (1-58), to “classical materials” lurking in The Temple but often their intentional or actual presence is debatable. Elsewhere Rickey’s expositions demonstrate the thoroughness of Herbert’s disguisings, as in the Christianizing in “Jordan” (I) of the “painted chair” attributed to Plato, and of Ariadne’s “silk twist” in “The Pearl”. Herbert’s democratic renunciation of classical references is not confined to his English poems. Musae Responsoriae, his series of epigrams against Andrew Melville’s Puritan polemic, begins with an elaborate dedication to James I, but the last poem adopts the simpler convention of The Temple by rededicating everything that Herbert writes to God: “Quod scribo, & placeo, si placeo, tuum est” (Drury and Moul, George Herbert, The Complete Poetry, Moul, 254 and 514-15). “The Forerunners” reiterates this decision in sprightly English: “He will be pleased with that dittie; / And if I please him I write fine and wittie.” Within Herbert’s Latin corpus classical allusions are most obtrusive in satiric poems such as the dialogue against Pope Urban VIII in Lucus (Nos. 25-28, Moul, 272-75). However, Herbert regarded some subjects as too sacred for such intrusions, even in Latin poetry. None occurs for example in Passio Discerpta (Moul, 289-301), a reworking of medieval Passion meditations that ends by inviting Plato to adopt the crucified Christ as the “anima mundi” (world soul).

[21] See Wilcox, English Poems, xli-xlv and 588.

[22] Eliot praises the “masterly simplicity” of “Praise” (II) (George Herbert 38).

[23] Rickey, Utmost Art, 151; my italics.

[24] The name may have had Herbert’s authority — see Wilcox, English Poems, 247.

[25] Wilcox, English Poems, 644-45.

[26] Vendler, Poetry, 203.

[27] See Bloch, Spelling the Word, 21-22.

[28] This movement similarly engaged Gerard Manley Hopkins, Herbert’s successor in English spiritual poetry: “It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil crushed” (“God’s Grandeur”).

[29] See Wilcox, English Poems, xlii-xliii.

[30] Wilcox quotes John 17. 21 where Jesus prays for unity among his disciples: “That they also may be one in us,” but Herbert’s prayer in “Clasping of Hands” isn’t for Christendom but for himself. C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, Letter 8, 31, describes theism as follows: “When He [God] talks of their losing their selves, He means only abandoning the clamour of self-will; once they have done that, He really gives them back all their personality, and boasts (I am afraid, sincerely) that when they are wholly His they will be more themselves than ever.” The monism of Herbert’s “Or rather make no Thine and Mine!” emerges clearly by contrast.

[31] Hodgson, ed. Cloud, 20, lines 5-7.

[32] See Fish, “Self-Consuming Artefacts,” 156-58.

[33] E. g., The Book of Privy Counselling in Hodgson, ed. Cloud, 152, line 17.

[34] Strier, “Herbert and Tears,” 224.

[35] Hodgson, ed. Cloud, 152, lines 9-10; see Taylor, “Paradox upon Paradox,” 31.

[36] Weil, Waiting, 68-69.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bloch, Chana. Spelling the Word: George Herbert and the Bible. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Clarke, Elizabeth. Theory and Theology in George Herbert’s Poetry: ‘Diuinitie, and Poesie, Met’. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Collected Letters. Edited by Earl Leslie Griggs. 6 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956-1971.

John Drury and Victoria Moul, eds., George Herbert, The Complete Poetry. UK: Penguin Random House, 2015.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 1921. “The Metaphysical Poets.” Times Literary Supplement, 20 October 1921, 669–70.

———-. Collected Poems 1909-1962. London: Faber and Faber, 1963.

———. George Herbert. Introduced by Peter Porter. Writers and Their Work. London: Northcote House in Association with the British Council, 1994.

Fish, Stanley. ‘Self-Consuming Artefacts’: The Experience of Seventeenth-Century Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

Hodgson, Phyllis, ed. The Cloud of Unknowing and the Book of Privy Counselling. Early English Text Society. London: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Hutchinson, F.E., ed., The Works of George Herbert, rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1945.

Johnson, Samuel. Lives of the English Poets. Vol. 1. London: Dent, 1961.

Lewis, C. S. The Screwtape Letters. London: HarperCollins, Fount Paperbacks, 1998.

MacDonald, George. ‘The Hands of the Father.’ Unspoken Sermons, First Series. 1867. Edited by David W. Sloan. Regimen Books. Northport Alabama: Vision Press, 2020. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/9057/pg9057-images.html

McCloskey, John and Paul R. Murphy, eds, The Latin Poetry of George Herbert. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1965.

Michael Leunig Appreciation Page. https://www.facebook.com/MichaelLeunigAppreciationPage/

Rickey, Mary Ellen. Utmost Art: Complexity in the Verse of George Herbert. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1966.

Strier, Richard. “Herbert and Tears.” English Literary History 46 (1979): 221-36.

Vendler, Helen. The Poetry of George Herbert. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Weil, Simone, Waiting for God. Translated by Emma Craufurd, introduced by Leslie A, Fiedler. New York: HarperCollins, 1973).

Wilcox, Helen, ed., The English Poems of George Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007; repr. 2013.

Responses to George Herbert’s Simplicity

Since the first publication of The Temple in 1633, fellow poets and critics have commented diversely on the perceived simplicity of George Herbert’s verse. Their responses have differed widely in terminology, analysis and definition. “Simplicity” heads a nexus encompassing “plainness,” “homeliness,” “directness,” “sincerity” and “purity.” This post gathers together a selection of views and quotes on the topic of Herbert’s simplicity. (more…)

Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Tom Stoppard once described his artistic goal as follows:

I realized quite some time ago that I was in it because of the theatre rather than because of the literature. I like theatre, I like showbiz, and that’s what I’m true to…. I’ve benefited greatly from Peter Wood’s [a London theatre director] down-to-earth way of telling me, ‘Right, I’m sitting in J16, and I don’t understand what you’re trying to tell me. It’s not clear.’ There’s none of this stuff about, ‘When Faber and Faber bring it out, I’ll be able to read it six times and work it out for myself.’ (Quoted Hayman, p. 8)

Some of us are drawn to solving play-puzzles, so I hope that this introduction to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (which I confess, I have read at least six times) proves helpful. This is an honest and funny play. Stoppard brilliantly revisits Shakespearean notions of life and death. (more…)

An Introduction to Colette’s The Cat

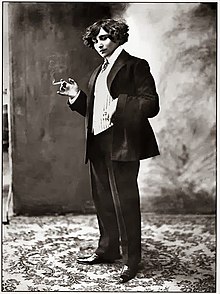

Page references in the following discussion are to Antonia White’s translation of The Cat in Colette. Gigi and The Cat. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1958. The Cat (La Chatte) was first published by Bernard Grasset, Paris, in 1933. This photo of Colette is by Henri Manuel:

Colette

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette (1873-1954) was a prodigiously productive writer of plays, novels, film scripts, reviews and short stories. English readers know her mostly for her novels, which have been available in translation for a long time, published by Penguin, and also made into films. She is, or was, as well known worldwide for her scandalous love life as for her writings.

Colette’s fiction falls into the three groups of her early Claudine novels, written before 1910 under the domination of her first husband, Willy; her mature works of the twenties and thirties, such as La Maison de Claudine (My Mother’s House), La Naissance du Jour (Break of Day) (1928), and La Chatte (1933); and works of the forties, in which she depicts her old age, such as L’Etoile Vesper (The Evening Star) (1946). Gigi, the second novel in your volume, was also first published in this period (1944).

The Cat

The introduction to the French edition of La Chatte locates it in a relatively tranquil period of Colette’s life, after she had survived her first marriage, and her love affair with Mathilde de Morne, named Missy, and was established in a relationship with Maurice Goudeket, 16 years her junior, whom she married in 1935, and to whom she remained attached until her death.

A writer on The Cat, Melanie Hawthorne, concludes her article, published in 1998, by noting that: “The ambiguity of La Chatte makes any definitive conclusion impossible, but in examining the political dimension of this novel, one might be forced to agree that “ce [n’]est [pas] si simple, c’est si difficile” (367). Hawthorne’s article nevertheless hints at a connection between Alain’s attitudes and Colette’s reputed, but not confirmed, sympathies with right-wing Nazi attitudes to class, gender and race in the period between the World Wars. Conversely, Hawthorne points to characteristics of Camille which “served to identify the modern woman who came to symbolize the loss of everything familiar in post-war [that is, after World War I] France” (363). This means that the reader’s sympathies are with Alain and against Camille. Hawthorne’s reading tends to revert to biographical responses to The Cat as a reflection of Colette’s well-known longing for the lost gardens of her Burgundian childhood, following her early first marriage and transportation to Paris. Under such interpretations, Alain’s empathy with Saha is similarly assumed to be a positive reflection of Colette’s even more famous love of cats. To quote Hawthorne for the last time, The Cat “is often viewed as a frivolous love story, as an illustration of Colette’s affinities with animals and nature” (361).

In this lecture I argue against this view of the novel. My argument is that language use and symbolism in The Cat undermines most of Alain’s attitudes, and validates Camille, both for being who she is and for her approach. I don’t claim much originality in arguing this view. The position is taken up by Marianna Forde, in an article published in The French Review in 1985, and she refers to other critics who arrived at similar conclusions about the novel.

I’m encouraged in my interpretation of The Cat by a reversal that occurs in the commentary by a conservative earlier critic, Margaret Davies. Davies’s opening summary of the plot reads: “Alain, the young man, runs away from the hard, shiny young girl, who as his wife is going to make a man of him, into the secure shadows of the heady garden of his childhood, seeking the ethereal, mobile presence of the cat which surges out of darkness like a spirit, accomplishing miracles of grace and movement, as beautiful as a demon” (86). However, at the end of her discussion, Davies writes:

It is, in fact, Alain who is the monster, having definitively chosen the ideal instead of the human, the Lost Paradise of the past instead of the vital force of the present. Life, life itself is the goal, even poetry can be withdrawal, abnegation. Colette had always known her own temptations and had always been able to write them out of her system” (89).

Narrative Viewpoint

Theorising about The Cat by Mieke Bal, referred to by Hawthorne, summarises the narrative position: “[The Cat is] told in the third person from the point of view of a character [Alain]” (362). In the process of “focalisation,” or more simply, focus on the internal life of one character, “the focalizer [or narrator] assumes the character’s view but without thereby yielding the focalizing to him” (362; my italics). In other words, the narrator remains outside of and detached from Alain, and invites us as readers to do the same. I would suggest that the focus on Alain should not be seen to imply that his attitudes are desirable; they do not invite the reader to sympathise with him uncritically. On the contrary, I suggest that the details that we discover about Alain’s inner and outer life are a warning on what to avoid. Alain exemplifies the crippling effects, bordering at times on absurdity and comedy, of self-absorption and the failure to mature. This is an awareness which The Cat conveys subtly to readers over the course of the narration, through an accumulation of narrative and descriptive details. The reader’s final realisation of Alain’s self-imposed narrowness seems to me to be all the more powerful, because of the initial impulse to identify and sympathise with him, engendered by the narrative perspective.

An interesting feminist paper could be written about the “male gaze” in relation to The Cat. You will have noticed in reading that one of the principal aspects of Camille which Alain dislikes and fears, because they penetrate his solitude, is her large eyes: “Catching sight again in the looking glass of the vindictive image and handsome dark eyes which were watching him” (67). Eyes pervade Alain’s delicious, self-chosen dreams—they belong to monstrous faces and people (71-73). Notice too Alain’s reaction to Camille’s photo, especially “her eyes enormous between two palisades of eyelashes” (74). This is a typical introvert’s dislike of being looked at, stemming I think from an only child’s experience of the parental gaze. Aldous Huxley refers to this in one of his early novels. Perhaps Alain identifies so closely with Saha because her eyes are impenetrable, invulnerable to the gaze of others. “Those deep-set eyes were proud and suspicious, completely masters of themselves” (68).

Under a feminist reading, a leading irony of The Cat is the fact that while Alain so much dislikes being looked at, he himself gazes constantly at Camille, and sits in judgment on her. It is this perspective that we as readers share for almost the whole length of the novel. As Forde points out, Alain is typically placed in static positions, viewing platforms from which he constantly looks at Camille, who is almost always presented as a being in motion. Alain therefore perpetrates on Camille the same intrusion by gaze, the same penetration, which he so strongly resists Camille imposing on him.

It is only in the final paragraph that this perspective is reversed, and we are allowed for the first time to look at Alain through Camille’s eyes, which he has considered throughout the novel to be so large and threatening. This reversal exposes a deep irony which has been hidden until now. The final insightful view, in which Alain at last becomes the observed, and not the observer, is highly significant. The cat, Saha, “was following Camille’s departure as intently as a human being”: Alain’s human gaze has been replaced by the impenetrable and invulnerable stare of the cat. Conversely Alain “was half-lying on his side, ignoring it. With one hand hollowed into a paw, he was playing deftly with the first green, prickly August chestnuts” (157). Alain has taken on the cat’s playful, self-sufficient and self-absorbed detachment. In the cat’s humanness and Alain’s likeness to a cat, it’s as if a final merging has occurred, confirming and hardening Alain’s egoistic stance, and even making it permanent. The green, prickly winter fruit of the chestnuts seems to symbolise both the end of this summer of opportunity—the marriage has lasted through the summer months, from May to August—and the coming of winter. The fruition suggested by the married state has not come to pass. However the unpromising winter harvest of the chestnuts may perhaps foretell a limited fruition in Alain’s future life.

Major Symbols

(i) Saha – The Cat

Both narratorially and symbolically, Saha accrues to Alain and is inimical or hostile to Camille. The union between young man and female cat has a sexual dimension. When Saha bites Alain, “He looked at the two little beads of blood on his palm with the irascibility of a man whose woman has bitten him at the height of her pleasure” (76). However, in truth, this is a pseudo-sexual rather than a sexual relationship; it’s a connection which evades the responsibilities that inevitably attend adult sexual relationships.

Later we read that “The admiration and understanding of cats was innate in him” (79). Camille is puzzled by Alain’s ability to understand what Saha is thinking and feeling (99). To her Alain’s relationship with and empathy with Saha is abnormal (139). It is clear that for Alain, Saha embodies something deep in himself, probably his “solitude, his egoism and his poetry,” to quote a list that occurs on p. 123. It’s significant later on that Alain’s mother refers to Saha as his “chimera” (151). A chimera is both a monstrous animal made up of the parts of other animals, and “a wild or unrealistic dream or notion.” For Alain, Saha is both monstrous and the embodiment of his unrealistic hope of remaining forever untroubled and insulated from life, like a child.

The manner in which the cat is discussed in relationship to Alain seems frequently to verge on the ridiculous, as if a subtle distortion in his viewpoint were being exposed. The way he addresses her: “My little bear with the big cheeks. Exquisite, exquisite, exquisite cat. My blue pigeon. Pearl-coloured demon” (70). (Demon is another interesting word, with connotations of the Greek daemon, or poetic inspiring spirit, and of course also devil.) “Ah! Saha. Our nights…” (71). Note the bathos, snobbery and egoism of the speech at the top of p. 80. It seems to me that this speech is an expose of Alain’s world view. Another ridiculous statement occurs after Alain has finally left the apartment and his marriage, when he is contemplating his restored connection at home with Saha: “He held her there, trusting and perishable, promised, perhaps, ten years of life. And he suffered at the thought of the briefness of so great a love” (145). Although the first sentence appears to invite the reader’s sympathetic approval, the second seems to go just a little too far, and wickedly to invite us to judge the situation from a more rational perspective—that of a narrator who does not cohere with the character’s viewpoint. The writing is a subtle exposé of deluded egoism.

A similar commentary can be applied to the language used about Camille after she has pushed the cat off the balcony: “A poor little murderess meekly tried to emerge from her banishment, stretched out her hand, and touched the cat’s head with humble hatred.” (132). “He lowered his head, imagining the attempted murder.” (140) “Thrown from the height of nine stories,” Alain thought as he watched her. “Grabbed or pushed. Perhaps she defended herself…perhaps she escaped to be caught again and thrown over. Assassinated.” (148-49) Perhaps we are on Alain’s side as he imagines Saha’s struggle for life. However, the last word, “Assassinated,” surely goes too far, and reminds us that after all it is a cat, and not a human being that is being referred to. Once again, our sympathy suddenly runs up against a sense of proportion, confronts reality.

(ii) Alain’s Home

(Much of this discussion is indebted to Marianna Forde’s article, “Spatial Structures in La Chatte” which I recommend to you. Forde discusses binary oppositions associated with Alain and Camille: down/up, closed/open, static/dynamic, past/future, old/modern, noble/common, living/dead.

1. Garden

The garden in suburban Paris at Neuilly is low down, five steps lower than the house branch. Forde considers in depth the significance of Alain’s association with the earth, with low places such as the garden and the house, the worn old servants, who are half-buried in their basement (105), and Camille’s contrary associations with height and open spaces. The garden is not usually presented in positive terms, but is associated, as in the first description (64) with blackness, or dark green, with fossilisation (calcined twigs), and old age. An iron fences walls it off from the real world (68). Far from being a place of fruition, the garden is presided over by a dead yew tree, which is mentioned no fewer than four times. Yew trees traditionally grow in cemeteries. Forde points out that a long hanging cluster of the poisonous laburnum hangs directly in front of Alain’s window (69). She suggests that the garden is in fact poisonous to Alain, because, like his attachment to Saha, it contributes to the stunting of his emotional growth. It protects him from the full gamut of adult experience. The prevalent colours of the garden are dark green and black. When colours other than these are associated with the garden, the effect is not so enchanting (145, bottom).

Other negative associations are with over-cultivation and over-civilisation, not in a good sense: “the secret exhalation of the filth which nourishes fleshy, expensive flowers” (90). There’s a sense of fossilisation, of the same summer scenes being acted and re-enacted again and again (92). The garden is also associated with age: “One of the oldest climbing roses carried its load of flowers, which faded as soon as they opened” (95). At his breakfast of “liberation” Alain receives “an ill-made, stunted little rose” (147).

2. Servants

There is a repetitive emphasis on the age of the servants, Emile the butler, and Juliette, the Old Basque woman with a beard. The physical descriptions of these are always negative, e.g., “The old butler muttered answers as shallow and colourless as himself” (94); “he raised his pale, oyster-coloured eyes, which had never laughed in their life, to the pure sky” (94).

3. Alain’s Room

The theme which merges most strongly in the depictions of Alain’s room, and himself in it, is his undeveloped childishness, his adolescence which is continuing into his twenties. The connections made between Alain and childhood, adolescence and childishness are innumerable in The Cat. When Alain reaches his room, he examines his face in the mirror, in a passage which demonstrates his self-obsession, if not narcissism (70). The box of ancient childish treasures, “bright and worthless as the coloured stones one finds in the nests of pilfering birds” (69), which he refuses to discard likewise suggests his refusal to let go of the past, a comment follows on his life as an only child (top of 70). At the end, when Alain returns to the setting of his pampered youth, his mother welcomes him by treating him again like a child (bottom of 149), and the old servants fall again into the patterns of a lifetime by serving “Monsieur Alain.” There is however restraint and a certain perceptiveness in his mother’s reaction, especially in her knowledge that a man has to be born many times with no other assistance than that of chance, of bruises, of mistakes (150-51). Like Alain, she nevertheless condescends to Camille as a member of the middle classes, classes that are only partially redeemed by their wealth (151).

Camille

It is important to distinguish between the information which the narrator reveals about Camille and Alain’s judgmental and resisting responses. That we as readers are invited to judge Alain for his judging of Camille seems plain from one of the early descriptions, in which it becomes clear that Alain prefers the shadow to the flesh-and-blood woman (65):

Unclasping her hands, the girl walked across the room, preceded by the ideal shadow… ‘What a pity!’ sighed Alain, Then he feebly reproached himself for his inclination to love in Camille herself some perfected or motionless image of Camille. This shadow, for example, or a portrait or the vivid memory she left him of certain moments, certain dresses” (65-66).

At this point, Alain is in a typically lowered, static state, watching Camille, who is dynamically moving about.

When Alain selects a photo of Camille for his bedroom, it is one “which bore no resemblance to Camille or to anyone at all” (74). The photo is of someone with accentuated features, “her painted mouth vitrified in inky black” (74). You should notice that this does not accurately describe the physical Camille. Camille’s make-up is not presented as hardening her or making her brittle. On the contrary, there is approval implied, both of her manner of self-presentation and of her body itself. Alain breathes in , “under a perfume too old for her, a good smell of bread and dark hair” (68). “Made-up with skill and restraint, her youth was not obvious at the first glance” (81). Cf. Also 95. “She was looking pretty every evening at that particular hour; wearing white pyjamas, her hair half loosened on her forehead and her cheeks very brown under the layers of powder she had been superimposing since the morning” (100). The vivid colours of life are captured (101) in the description of Camille laughing as she eats the melon. Alain detects, “how vivid a certain cannibal radiance could be in those glittering eyes and on the glittering teeth”; but this reaction opposes the other part of the description, and the reader is not obliged to agree. On the contrary, what the make-up does imply, is Camille’s wish to be attractive and pleasing to Alain. Cf. 85. In fact, her longing that he will love her spontaneously is obvious in almost every encounter, and in every encounter he hangs back.

Alain’s dislike of Camille’s natural and uninhibited sexuality, his repugnance at her parading around in the nude is undercut by the subtle revelations which are given, twice at least, that he has had mistresses in the past. The scene of the morning after their wedding night (83) is a none-too-subtle revelation of Alain’s judgmental snobbery: “She’s got a common back…She’s got a back like a charwoman.” Such comments are juxtaposed with Colette’s positive presentation of Camille’s physical grace: “But suddenly she stood upright again, took a couple of dancing steps and made a charming gesture of embracing the empty air.” Lightness and airiness typify descriptions of Camille. Alain’s sense that Camille is becoming fat while he becomes thinner by lovemaking is presented, significantly as the “age-old misogynist complaint.”

The Wedge

While Alain is at home on and below the ground at Neuilly, the airiness of the Wedge, a modern apartment on the ninth floor of a building called Quart-de-Brie is associated with Camille. The obvious triangular symbolism of the Wedge, with the tops of the three dying poplar trees visible outside (101), an indication perhaps of the ménage à trois formed by the two humans and the cat, is typical of the subtle symbolism operating throughout The Cat. The Wedge is open to breezes, which are never still (93). While Camille enjoys its openness to the elements, Alain tends to hole up there, especially in the little annex where he sleeps on the hard narrow bed, “the waiting room bench.” He brings in the pot plants to protect them from the wind.

The fireworks watched from the Wedge (135-37) may symbolise the brilliance and transience of Alain and Camille’s love. Despite the orgasmic connection, I think that the rockets are more closely connected with Camille’s unhappiness as she realises the hopelessness of her relationship: “It never lasts long enough,” she said plaintively (136). “No. It’s you. It’s you who… who don’t love me” (137). If we’re tempted to condemn Camille as the attempted murderer of the cat, it’s scenes and words of hers such as these that we should look at. In fact the near-homicide of the cat was the culminating act in Camille’s attempts to save her marriage, attempts that typify all her interactions with Alain from the very beginning. It’s a big and energetic act, which contrasts strongly with Alain’s predictable horror and condemnation. Consider the ridiculous over-statement on 155, “A little blameless creature etc….”

After she arrives at the Wedge, Saha follows Alain in avoiding the winds, though, like Camille, she passes her time watching from the balcony and shows no fear of heights. The culmination of Alain’s reaction against the Wedge comes in his fear of the storm. He seeks Camille’s protection, but characteristically withdraws when the storm is over. Few of us indeed get through life without facing storms, a truth that it would profit Alain to keep in mind.

Discussion Topics

1.Discuss the possible significance of eyes, dreams, gardens, the number three. Any other symbols?

2.Which does Saha most resemble – Camille or Alain? Or is it that they resemble her? (Which is primary?)

3.Discuss Saha as “character” and as symbol.

4.How do you feel about Camille’s attempted murder of Saha?

5.Discuss the representation and significance of subsidiary figures in The Cat, e.g. the parents, especially Alain’s mother; and the servants.

6. What feminist assumptions do you find in The Cat? Or, does the novel invite the reader’s sympathy for Alain? What, if anything, is unappealing about Camille?

7. Assuming that they are symbolic, what light do the roadster and the rockets cast on the contrasting characters of Camille and Alain?

8. Discuss ambiguity in The Cat.

9. Discuss The Cat as a despairing comment on heterosexual connection.

Colette’s The Cat: Selected Studies

Callander, Margaret M. Le Ble en herbe and La Chatte. Critical Guides to French texts. London; Valencia : Grant & Cutler; Artes Graficas Soler, 1992.

Davies, Margaret. Colette. Writers and Critics. Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1961. [The Cat 85-89]

Dormann, Genevieve. Colette: A Passion for Life. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984. [Colette in pictures!]

Forde, Marianna. “Spatial Structures in La Chatte.” The French Review: Journal of the American Association of Teachers of French, Champaign, IL (FR). 58:3 (1985): 360‑367.

Hawthorne, Melanie. “’C’est si simple… C’est si difficile’: The Ideological Ambiguity of Colette’s La Chatte.” Australian Journal of French Studies (AJFS). 35:3 (1998): 360‑68.

Ladimer, Bethany. “Moving Beyond Sido’s Garden: Ambiguity in Three Novels by Colette.” Romance Quarterly, Washington, DC (KRQ) 36:2 (1989): 153‑167.

George Herbert: Poet and Spiritual Guide

George Herbert (1593-1633) belonged to the school of seventeenth-century which included John Donne, Henry Vaughan, Richard Crashaw, Abraham Cowley and Thomas Traherne. Helen Gardner’s introduction to her edition, The Metaphysical Poets (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966), is an expert discussion of the leading features of this school. Present-day Bemerton residents have provided an excellent illustrated biography of Herbert: http://www.georgeherbert.org.uk/about/ghb_group.html. I highly recommend also Amy M. Charles, A Life of George Herbert (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press,1977). Guides to some of Herbert’s best-known and best-loved poems follow. (more…)

Jennifer Rogers: Jigsaws

Jigsaws was first performed at the Hole in the Wall theatre in Perth in 1988. It was published by Currency Press in the same year. A season at La Boite Theatre, Brisbane, followed in January-February 1990. See the plot outline and photo of performers at <archive.laboite.com.au/1990/jigsaws> . Jigsaws was revived at the Koorliny Arts Centre, Kwinana, WA, February 12 – 27, 2013. All the characters are women–a rarity in the traditional theatre and a feminist statement in itself.

George Johnston’s My Brother Jack

These three lectures trace themes of war, soldiership, masculinity, femininity, and family relationships as they unfold sequentially through My Brother Jack.

LECTURE ONE: BOYHOOD

My Brother Jack was first published to critical acclaim in 1964. It follows the lives of David Meredith and his brother Jack from David’s childhood in 1914 (when he was three) to 20th March 1945, when British forces recaptured Mandalay, Central Burma, from the Japanese army. The lives of the two leading characters are deeply affected by the two world wars and by the world-wide Depression of the early 1930s. Johnston also explores ways in which these events affected Australia more generally. More particularly, his novel documents changes in family and suburban life over the thirty-year period. My Brother Jack considers complex issues of male self-definition, of ethics and family relationships.

The following are among the questions raised:

- War is a disaster, but does it possess the positive aspect of providing essential self-definition and a cause for men like Jack?

- Is Jack presented unequivocally as an ideal Australian man?

- What are the qualities of the ideal Australian man?

- If Jack embodies this ideal, where does that leave David?

- How justified is David’s sense of himself as weak and selfish and of Jack as strong, outgoing and affectionate?

- Does the fact that he has a sensitive conscience exonerate David?

- How justified is David’s guilt about his own social and material success in relation to Jack’s failure in these spheres?

- How do you define a man’s failure or success?

- What gender issues are raised by this novel?

- How does the ideal of a man as a brave fighter fare in My Brother Jack?

- “In My Brother Jack individual morality is the primary interest, overriding themes of heroism, war, definitions of manhood, and representations of the Australian national character.” How far do you agree?

The Young David Meredith

The character of David Meredith is a key for interpreting My Brother Jack. We’ll begin our exploration therefore by mustering and exploring clues about David’s character. Since Jack is the main reference point for David’s characterisation, we’ll also be discussing him.

Two further questions concern David as narrator:

- How reliable is he, especially as a judge of merit and character?

- Is the reader able to read between the lines of what David reveals and arrive at judgments of himself and Jack that differ from David’s own?

Childhood